A Conant teacher’s passion for La Salle’s expedition, and how he still hasn’t given up

Forty years and 3,300 miles later, chemistry teacher Richard Gross still isn’t satisfied. When asked what he will be doing after he retires this year, he proudly says he will continue on his search to find the late French explorer Robert de La Salle’s lost ship, The Griffon.

“I’m very excited for retirement,” Gross said, “because then I’ll get to devote all my time to looking for that ship.”

The beginning of his passion

Gross’s interest in La Salle began when, 42 years ago, his French teacher Reid Lewis announced that he needed student volunteers for a special trek he was conducting.

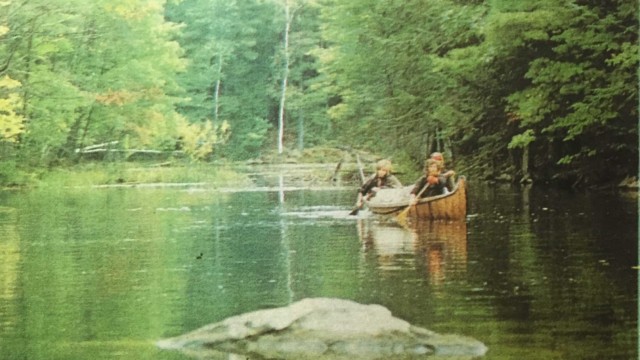

They were going to recreate La Salle’s exploration of the United States, starting in Montreal, Canada and ending at the Gulf of Mexico. According to the 1978 August/September issue of Mariah, an outdoor magazine, “In 1681-82, La Salle led the epic canoe expedition that claimed the American heartland for Louis XIV and France.” Similarly, Lewis’s recreation lasted eight whole months and 3,300 miles, which would be covered by foot and canoe. It was called La Salle: Expedition II.

“The goal of the trip was to do everything La Salle and his men did,” Gross explained. “That means no cars or modern technology.”

After hearing that they would have to take a year off after graduation in order to a part of the journey, many backed out, but Gross remained interested.

“It intrigued me from the start,” he recalled. “I had heard about Mr. Lewis and the cool things he did, and I was so excited to participate.”

Gross says the trip was conducted at the best time because 1976 was the year of the United States Bicentennial.

“There was no better time to show everyone America’s French roots,” Gross said. “Everyone thinks all our history is English, but that’s not true.”

Gross signed up to be a participant in the trip during his junior year, and through his last two years of high school, he trained for it.

The team prepared by learning how the explorers in the 1600s lived: what their daily lives were like, what they wore, and what they ate. They even built canoes and muskets. By the time of the trip, the team mastered canoeing and camping techniques, the French language and memorized all voyager songs.

“I built my own canoe, musket, moccasins, and many other things,” Gross said proudly. “It was hard at the beginning, but I got to learn something new.”

The canoes were each 20-feet-long with a fiberglass shell, and the moccasins were made from leather.

In addition, women’s clubs helped the participants prepare by knitting clothing for them. The participants especially needed warm coats to keep them safe from the frigid winter they would go through on the expedition.

“[In terms of clothing], I had what I was wearing and another pair to change into,” Gross said. “My gear included leather moccasins, socks, underwear, pants, shirts, a vest, a hat, a finger woven sash to function as a pocket, and a big coat made from blankets.”

The crew even had a physical training director, Dick Stillwagon.

“Our cardiovascular conditioning program was built around Kenneth Cooper’s concept of aerobics,” Stillwagon explained.

The recruits went through many running exercises.

“We had to go through a lot because we’re not used to all that walking,” Gross said. “La Salle’s crew probably found their trip to be a lot simpler than we did.”

In addition, Lewis tested his recruits before deciding who he would take on the trip. He did this by requiring the boys to go through team-building activities and do quick problem solving on their feet. A team psychologist was also hired to help figure out who would make the cut.

Gross was one of the 16 students that qualified out of the 65 that signed up.

“[I chose Richard because] he is an extrovert and very good at analyzing situations,” Lewis explained. “He listens to understand, not to respond, which is a lot like employing the scientific method.”

Lewis also said that he liked Gross’s ability “not to prejudge things” and was delighted to have him on the journey.

After graduation, a group of eight adults and 16 high school grads began on the trip.

The expedition

The trip began with eight adults, 16 students, and a liaison team driving up to Montreal, Canada. From there, everyone but the liaison team ditched the cars and started to trek into the United States. On average, the team tried to cover as many miles a day as they could, Gross said.

Every 1-2 days, they would head into a different town and set up camp. The liaison team would coordinate the visit beforehand, so the townspeople would be expecting them. There they would be treated to a feast and get to wash their clothes. They would also inform people about American-French history, Gross recalled.

“We would perform skits, reenact battle scenes, sing songs, and play music that was all related to French history. It was a great way to involve the community around us,” Gross explained.

Lewis said that they spread their message through the media as well.

“Our message was shared through TV news stations and newspapers too,” he said. “So if we didn’t stop by the town, people still knew what we were doing.”

“Besides reenacting the voyage,” he continued, “we were also interpreting it to the communities along our route, and using it to dramatize our journey with historical and environmental preservation.”

In addition to visiting towns, the team also visited schools and universities, where they presented to students of all ages.

“The presentation was a tremendous success,” said Dr. Paul R. Bernard, the Modern Language and Classics head at Saint Mary’s University, one of the many schools the team visited.

“The voyager music in background sound effects were clearly interwoven into the show and created a realistic impression; the composition and organization of the material highlighted extremely well the similarities and points of divergence between the 17th and 20th century life,” Bernard added.

Lewis said Kelly Stelzriede, a student from Colorado, personally sent a letter to him, explaining how impactful the presentation had been. She explained how she had been struggling in school, but the presentation inspired her.

She said, “My struggle didn’t end that day, but [the presentation] added strength to my dwindling supply.”

Gross and Lewis both said the trip allowed Americans to get involved with their own history, and that meant doing an authentic reenactment with real physical and emotional challenges, and the very really possibility of failure.

Gross also said that he anticipated the trip would be difficult, but he had no idea until the actual journey. He explained, “I was young, and it was challenging, but it was one of the greatest experiences of my life.”

Gross said he had to mentally fight through the challenges he faced. He described his daily struggle with his moccasins. “Since it was so cold, they would always freeze up,” he said. “We would always be around the fire at night to defrost them, and make sure we didn’t get sick, but someone always ended up getting a cold.”

In addition to the low temperatures, Gross talked about the food he had to eat: cornmeal, peas, and beans. One of the main differences between La Salle’s expedition and Gross’s trip was a lack of meat. La Salle’s men hunted for the meat, but the 20th century explorers did not.

“I really, really hated the food,” Gross said. “But the towns we went to gave us warm meals, so it wasn’t all that bad.”

Moreover, Gross remembered that he was one of the few on the trip that didn’t get homesick. “I was really enjoying myself. While my mom was super resistant about me exploring, she was the one who had taught me to be this way, so I was having a great time out on the expedition.”

But the frozen moccasins and everyday beans were only a small challenge. Gross recalled some of the most difficult times, such as the time where four of his teammates were hit by a truck.

“It was very dangerous,” he said. “The river had completely frozen up, and there was no way to canoe on it, so we lifted the canoes over our heads and walked alongside the road.”

“It was foggy and snowing, and our dark clothes made it hard for cars on the road to see us,” he continued. “We were walking, and suddenly, a truck hits four of the guys.”

Gross explained that two of them made a full recovery and returned to the expedition fairly quickly, but the other two had injuries that forced them to leave the trip; one was forced to have his spleen removed. Fortunately, no one died because of the incident.

Some of the other dangers the team faced were not ones that explorers in the 17th century did. The Mariah described, “Once, they were forced to make an emergency bivouac in a field of unexploded bombs on a military testing range. Later, paddling southward on Lake Michigan, they watched the water change from drinkable to a puddling of oil and human waste. They had to dodge traffic on the Mississippi, rush-hour traffic on the streets of Toronto, and a snowmobile that ran amok and dove off a bridge at them on the Kankakee river.”

They overcame the natural and man-made dangers, remembering their tough preparation as they continued south.

“It got a bit scary in the winter,” Gross said. “But we kept our hopes up by thinking of the South. Everyday we were closer to the South, where it was much warmer. That’s how we got through it.”

Post expedition

After the expedition was completed, Gross said farewell to his crew mates and continued onto college, where he majored in biology. However, he says he still keeps in touch with his teammates, especially Lewis.

“He’s like an older brother to me,” Gross said. “And while I wasn’t best friends with all my teammates, I still remember them.”

Gross said that the trip helped him realize his passion for history, which is why he had continued to research La Salle’s journey over the last 40 years; however, his true love had always been biology. Gross said the trip made his love for biology grow even more.

“We had a biologist come with us on the trip,” he said. “He would take readings and other things, which made me love biology even more.”

In addition, Gross has also published scholarly articles on La Salle in Canadian professional journals. He has also disproven prior knowledge on La Salle’s trip and offered explanations of his own.

After successfully teaching science at Conant for 19 years, Gross says he is ready to retire, but he is not ready to give up on his quest to find The Griffon.

“If there is anything I’ve learned from this trip,” he says, “it’s that you can literally do anything if you put your mind to it. So I’m not giving up on something I love.”

i find the story of Lasalle II very inspiring and moving. Thanks for this article !